Published April 20, 2013, 12:00 AM

Athletes, scientists to tackle North Dakota Badlands to see oil boom affects

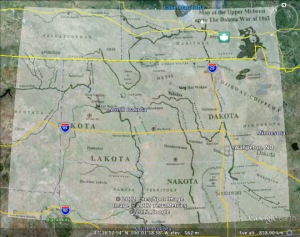

All in the name of science, a seemingly unlikely pairing of athletes and scientists will descend upon the North Dakota Badlands in an effort to catalog the area and determine if the oil boom is affecting the wilderness from the Killdeer Mountains to the Elkhorn Ranch to Sully Creek State Park, south of Medora.

By: Katherine Grandstrand, The Dickinson Press

All in the name of science, a seemingly unlikely pairing of athletes and scientists will descend upon the North Dakota Badlands in an effort to catalog the area and determine if the oil boom is affecting the wilderness from the Killdeer Mountains to the Elkhorn Ranch to Sully Creek State Park, south of Medora.

“Everything’s still set to go,” said Simon Donato, Adventure Science founder. “We’re not going to stop because of the snow, but it certainly added some considerations for us now.”

On Monday, Earth Day, Adventure Science will launch the first 100 Miles of Wild trip through the North Dakota Badlands.

A former ExxonMobil geologist who worked in the oil sands field in Canada, Donato is no stranger to oil development. He had heard stories about how oil development was encroaching on the wilderness of the North Dakota Badlands.

“Our whole project — it’s a neutral project,” he said. “We take no sides. We go out there objectively and just collect data. What we want to do out there is say, ‘OK, this area is going to be expanded into. They’re bringing rigs in, they’re building roads. What stands to be lost? What are they moving into? What are they moving over?’

“Until boots hit the ground, we don’t know what stands to be lost.”

Joining the Adventure Science team are archaeologists Andrew Reinhard, of Princeton, N.J., and Richard Rothaus, of Sauk Rapids, Minn. The duo had planned a camping trip to the North Dakota Badlands last year, but had to put it off when Rothaus broke his leg.

At the time Reinhard had never been to North Dakota, but had been backpacking in the other 47 contiguous states.

“It was 15 below out with no wind chill, which was a little crazy,” he said of his first trip to the state earlier this year, during the Punk Archaeology conference in early February in Fargo.

The Adventure Science trip will be his first backpacking experience here. Rothaus has been to the Badlands several times throughout his life and had been looking forward to the camping trip. When the pair talked about planning the Badlands trek again, they discussed the changes happening in the area and decided that their camping trip could be something more.

Rothaus and Reinhard had both completed Adventure Science trips before, and thought the North Dakota Badlands would make a perfect setting for a trip. They set about getting Donato on board.

“Now we’ve got a full-on expedition to go out and check the status of the wilderness,” Reinhard said.

The group will start in the Killdeer Mountains, head west to the Elkhorn Ranch and drop south to Sully Creek State Park.

“I have a real curiosity to see what’s going on in the wild spaces,” Reinhard said. “If what’s going on in the Bakken formation is affecting anything — maybe it is, maybe it isn’t we just don’t know.”

The scientists will start Monday and the athletes — who Rothaus and Reinhard admit move much quicker — will join Friday.

“We basically combine athletes and scientists to go tackle projects that most other people aren’t really interested in doing,” Donato said. “We take things out of the lab.”

The athletic team is comprised of ultra-marathoners and other endurance sport enthusiasts, Rothaus said.

The team has mapped out their route, including camping sites, although those might have to change due to snow and mud.

“If we have to search a little harder to find those ideal camp spots — right now we’ve got our route mapped and we’ve got the areas that we’d like to camp — we’ve got the coordinates selected for those already,” Donato said. “We will be fluid in the field in the sense that we’re going to kind of have to adapt on the fly if the area that we wanted to camp is a mud hole because of the snow.”

The snow and mud might make archeological finds more difficult, but should not alter the rest of their mission, Donato said.

The crew will still stay in tents overnight, but participants had to provide their own winter-camping gear before signing up, he said.

The team will not be completely alone; there will be support vehicles available for emergencies and to move equipment from site to site.

“We’re going in prepared for anything from tornados to blizzards,” Reinhard said. “If we need to bail out if things get really hairy, we’ll have support, which is really good.”

This will be the eighth mission led by Donato of Calgary, Albert, Canada.

Adventure Science’s first trip was a search and rescue mission after millionaire pilot Steve Fossett disappeared in the Sierra Nevada Mountains in 2008.

The team will be updating interested parties through online resources when available. For a complete list, visit www.adventurescience.ca.

http://www.bakkentoday.com/event/article/id/67687/publisher_ID/6/

“Everything’s still set to go,” said Simon Donato, Adventure Science founder. “We’re not going to stop because of the snow, but it certainly added some considerations for us now.”

On Monday, Earth Day, Adventure Science will launch the first 100 Miles of Wild trip through the North Dakota Badlands.

A former ExxonMobil geologist who worked in the oil sands field in Canada, Donato is no stranger to oil development. He had heard stories about how oil development was encroaching on the wilderness of the North Dakota Badlands.

“Our whole project — it’s a neutral project,” he said. “We take no sides. We go out there objectively and just collect data. What we want to do out there is say, ‘OK, this area is going to be expanded into. They’re bringing rigs in, they’re building roads. What stands to be lost? What are they moving into? What are they moving over?’

“Until boots hit the ground, we don’t know what stands to be lost.”

Joining the Adventure Science team are archaeologists Andrew Reinhard, of Princeton, N.J., and Richard Rothaus, of Sauk Rapids, Minn. The duo had planned a camping trip to the North Dakota Badlands last year, but had to put it off when Rothaus broke his leg.

At the time Reinhard had never been to North Dakota, but had been backpacking in the other 47 contiguous states.

“It was 15 below out with no wind chill, which was a little crazy,” he said of his first trip to the state earlier this year, during the Punk Archaeology conference in early February in Fargo.

The Adventure Science trip will be his first backpacking experience here. Rothaus has been to the Badlands several times throughout his life and had been looking forward to the camping trip. When the pair talked about planning the Badlands trek again, they discussed the changes happening in the area and decided that their camping trip could be something more.

Rothaus and Reinhard had both completed Adventure Science trips before, and thought the North Dakota Badlands would make a perfect setting for a trip. They set about getting Donato on board.

“Now we’ve got a full-on expedition to go out and check the status of the wilderness,” Reinhard said.

The group will start in the Killdeer Mountains, head west to the Elkhorn Ranch and drop south to Sully Creek State Park.

“I have a real curiosity to see what’s going on in the wild spaces,” Reinhard said. “If what’s going on in the Bakken formation is affecting anything — maybe it is, maybe it isn’t we just don’t know.”

The scientists will start Monday and the athletes — who Rothaus and Reinhard admit move much quicker — will join Friday.

“We basically combine athletes and scientists to go tackle projects that most other people aren’t really interested in doing,” Donato said. “We take things out of the lab.”

The athletic team is comprised of ultra-marathoners and other endurance sport enthusiasts, Rothaus said.

The team has mapped out their route, including camping sites, although those might have to change due to snow and mud.

“If we have to search a little harder to find those ideal camp spots — right now we’ve got our route mapped and we’ve got the areas that we’d like to camp — we’ve got the coordinates selected for those already,” Donato said. “We will be fluid in the field in the sense that we’re going to kind of have to adapt on the fly if the area that we wanted to camp is a mud hole because of the snow.”

The snow and mud might make archeological finds more difficult, but should not alter the rest of their mission, Donato said.

The crew will still stay in tents overnight, but participants had to provide their own winter-camping gear before signing up, he said.

The team will not be completely alone; there will be support vehicles available for emergencies and to move equipment from site to site.

“We’re going in prepared for anything from tornados to blizzards,” Reinhard said. “If we need to bail out if things get really hairy, we’ll have support, which is really good.”

This will be the eighth mission led by Donato of Calgary, Albert, Canada.

Adventure Science’s first trip was a search and rescue mission after millionaire pilot Steve Fossett disappeared in the Sierra Nevada Mountains in 2008.

The team will be updating interested parties through online resources when available. For a complete list, visit www.adventurescience.ca.

http://www.bakkentoday.com/event/article/id/67687/publisher_ID/6/